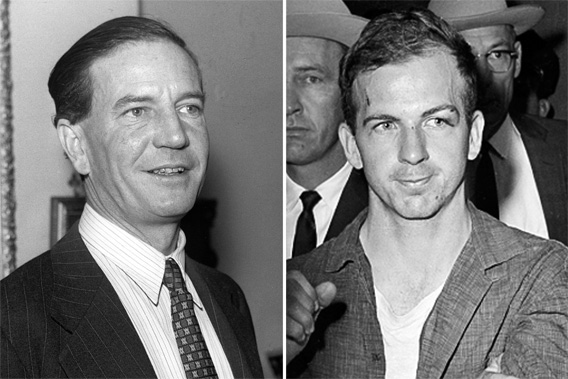

A November 1955 photo of Kim Philby, left, the "Third Man" in the Burgess and MacLean spy case. Lee Harvey Oswald, right, suspected assassin of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, at police headquarters in Dallas, Nov. 22, 1963.

A November 1955 photo of Kim Philby, left, the "Third Man" in the Burgess and MacLean spy case. Lee Harvey Oswald, right, suspected assassin of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, at police headquarters in Dallas, Nov. 22, 1963. Photo by AP, left; Photo by Ferd Kaufman/AP, right

Oswald and Philby. Lee and Kim.

?The Lone Gunman? and ?the Third Man.? We?re still haunted by the legacy of these spectral figures, their legacy of doubling and doubt?and, yes, the shadowy counterspy linked to both. At least I am. You should be too, since you live in a world of uncertainties they helped create.

Not just from their overt acts?Philby, long-term, high-level KGB mole inside British secret intelligence service (MI6), a double?or was it triple??agent shaping the origins of Cold War paranoia; Oswald, leaving a legacy of mystery, paranoia and conspiracy theory around himself, of the sort that has come to shroud so much alleged certainty about historical truths ever after. Is there any major event that now doesn?t come with its penumbra of YouTube conspiracy fantasies? The more you look the less (undisputed) truth you see.

The two of them (and the shadowy third whose identity I will disclose, I promise) exemplify a century of double agents, double dealing, double meaning, doubly ambiguous doubt about the public narrative of history, ambiguities that cloud or complexify conventional wisdom about the accepted narrative and suggest we are lost in ?a wilderness of mirrors.? And every once in a while something new turns up, a new twist, a declassified document, an overlooked defector, a forgotten witness.

As it has recently with both these enigmatic figures. A half-century after their defining moments on the stage of history, two new books have disclosed unexpected perspectives worth exploring.

1963: Fifty years ago, the year Kim Philby defected to Moscow, purportedly erasing any doubts he was a KGB mole. Although, in fact, the doubts persist in some circles, mainly in the form of theories that he was a triple, not a double, agent. That is, who was he really working for all those years, us or them? More piquantly: Is it possible even he didn?t know?that he had been set up and used? Questions too about exactly how he distorted the ?facts? he communicated to both sides at the origin of the Cold War, thus shaping or misshaping history.

1963: Fifty years ago, Lee Harvey Oswald does something in Dallas, the president?s head explodes, and soon Oswald is dead too. According to polls, more than half the nation still believes that if Oswald was involved at all in the shooting (not just, as he claimed, ?a patsy?) he was part of a conspiracy involving two shooters, even ?two Oswalds? or an ?Oswald impersonator? or two. But the true locus of mystery and generator of conspiratorial doubt is Oswald?s mind, that lonely labyrinth in which even he may have been lost. Whose side was he really on, was he a double agent, was he a player on his own stage, or was he being played? By whom?

I?ve spent a considerable amount of time exploring both enigmas. I thought that in my 12,000-word Philby investigation for the New York Times Magazine some time ago, I had exhausted the number of mysteries Philby set afoot with his double (or triple?) dealing. And I?ve written frequently on JFK theories, recurrently changing my mind on that morass of mystification; to my current belief Oswald was a shooter, though not ruling out the possibility of a second one, or silent confederates egging Oswald on to do the deed. But what an amazing legacy of paranoia he?s left us, what a vast spectrum of theories that seems to keep growing, concatenating.

Things seemed to have slowed down on that front, the high tide of conspiracy books receding (though not ceasing), the two camps?lone gunman vs. conspiracy?fortified in their opposing certainties with little or no new evidence on the crime itself emerging. I basically gave up thinking there would be anything new to emerge despite the likelihood that (as Jefferson Morley?s valuable investigative lawsuit claims) there are a large number of important documents on the case still classified.

But in the course of one week this winter I came upon two recent books that made me think the two cases deserve further thought.

A coincidence no doubt?as is the fact that the names of the authors of the two books?Lattel and Littell?are so similar (and end in the syllable for ?tell?). In this game one has to learn to distinguish between the meaningful and the meaningless coincidences.

The Oswald-related book, Castro?s Secrets, is by Brian Latell, a former top-level CIA agent charged with the debriefing of a high-ranking defector from Fidel Castro?s highly secretive intelligence agency, the DGI. The defector who came in from the cold in Vienna in 1987, a guy named Florentino Aspillaga, offered some remarkable inside DGI information about Oswald, the DGI, and Fidel that, if true, argues for a paradigm shift in Kennedy assassination theories. He also discloses substantiating material from a previous defector?information that was new to me.

Young Philby by Robert Littell

Young Philby by Robert Littell Courtesy of Thomas Dunne Books

The Philby book?Young Philby?is a unique (and strangely overlooked) historically-based spy novel by well-respected espionage writer Robert Littell (The Company and The Once and Future Spy among others, many of which suggest contacts within the intelligence community). It seeks to substantiate the possibility that Philby was more than a KGB mole, that in fact he may have served as a knowing or unknowing channel of information (and disinformation) for MI6 and the CIA?a theory I wrote about (and called ?unlikely?) in my investigation, but which Littell?no naif in these matters?clearly seems to believe. And he says he has a smoking gun to prove it.

Maybe we should start from the beginning. Harold Adrian Russell ?Kim? Philby, the Cambridge-educated scion of the British establishment, was the son of the once-famed Arabian explorer St. John Philby. According to most accounts, an Austrian sexologist and Soviet agent named Arnold Deutsch recruited Kim as a Soviet operative after he had left the leafy glades of Cambridge to consort with Austrian Communists (and marry one) during the 1934 street battles with fascists in Vienna. Philby?s mission: disguise himself as a right-winger and work his way up the old-boy network of the British ruing class on behalf of the NKVD (predecessor to the KGB). Kim was joined by a quartet of other like-minded college fellows later to be known as the ?Cambridge Five.? If you?ve read your le Carr?, you?ll recognize Kim as a good match in character at least for the mole, Bill Haydon, in Tinker, Tailor.

And boy did he succeed, getting recruited by an apparently oblivious (or were they?) MI6 as the second world war began, ending up after the war as the head of MI6?s Russian Division, thus making him the grand pivot man in the genesis of the Cold War?confirming Stalin?s belief in the evil plotting of the West, feeding the West a careful diet of disinformation about what the Soviets were up to. Or was it the other way around? Who got the info and who got the disinfo? Should we credit Philby and his other moles with preventing World War III?giving Stalin the security that his most paranoid fears (of a surprise nuclear attack) were unfounded, because he would have known from his moles if something was up? Or did both sides get what Philby chose to weave out of his own history-making imagination? (?Espionage,? le Carr? once wrote, ?is the secret theatre of our society.?)

Ultimately Philby was on the verge of becoming head of MI6?as I believe I was the first to confirm from a highly placed source?when the ?Third Man? affair fatefully killed his chances. Two of the Cambridge Five defected to Moscow in 1951, fearing they were about to be arrested, and suspicion fell on Philby for being the ?Third Man? who tipped them off. Philby was forced to resign and consigned himself to a purgatorial limbo in the Middle East where, under the watchful eyes of MI6, the KGB, and the CIA, he wrote for the U.K. Observer (and the New Republic, which was owned until 1956 by another former Soviet mole Michael Straight, not yet exposed). It should be noted that the famous Orson Welles-starring film The Third Man was written by Graham Greene and released in 1949, two years before Philby was named ?Third Man.? (Click here for more on the Graham Greene connection.)

Finally in 1963, MI6 felt it had enough evidence Philby had been a mole to confront him in Beirut. In what is still one of the most debated episodes in his career, he managed to?or was allowed to?escape to Moscow, where he lived until his death in 1988. Still, even in Moscow he was never fully trusted, according to former KGB colleagues I interviewed. As far back as 1948, an NKVD agent was compiling a dossier on Philby, attempting to prove that he was really a plant ? not a double but a triple agent actually working for MI6 to deceive the Soviets into thinking he was their mole. One ex-KGB source called this 1948 hellhound on Philby?s trail ?Madame Modrjkskaj,? said to be head of the NKVD?s British division, who ?came to the conclusion that Kim was a plant of the MI6 and working very actively and in a very subtle British way.?

Here?s where Robert Littell?s new novel takes up the case. The somewhat misleadingly titled Young Philby tells the Philby story in part from the point of view of a female NKVD analyst whose name Littell spells ?Modinskaya.? (I think the spelling is just a variant, not an attempt to fictionalize her.) And basically Littell?s novel concludes that she was right: that, yes Kim?encouraged by his scheming father, St. John Philby?was playing the triple-agent game on behalf of MI6. Littell (who did not respond to an email sent through his publisher to his residence in France) portrays Madame M. as being executed by Stalin for her suspicions of his prized mole, although I don?t know if this is historically based. But if she died, suspicions of Philby never did, and they haunted him even in his post-defection home in Moscow.

But what makes Littell?s book more a than just another twisty spy fantasy is the nonfiction epilogue, in which Littell tells of a fascinating encounter he had with Teddy Kollek, a figure most well-known as longtime mayor of Jerusalem, but who knew Kim as a young communist sympathizer in Vienna in 1934. And here?s where we meet our mysterious third figure: in a 1983 Harper?s piece I wrote about the way there were some who believed U.S. counterintelligence guru James Angleton had not been fooled by Philby, because Angleton had been tipped off by Kollek and?here?s yet another way of looking at the case?had deliberately fed Philby disinformation. Philby was then the dupe of Angleton, not the other way around. An unwitting triple agent.

People are prepared to believe that of Angleton because of his mythic reputation within the intel community as the Master of the Game?a reputation he guarded jealously. If Philby was, as many have called him, the spy of the century, James Angleton was the counterspy of the century. Legendary for having learned the complexities of the game from the study of ?seven types of ambiguity? as a Yale English literature scholar?he published High Modernists such as William Carlos Williams and Ezra Pound in his undergraduate literary magazine?he was notorious for pursuing suspicious ambiguities in the backstories of many defectors he believed were actually KGB plants. He would want to have people believe he was outfoxing Philby, not the other way around.

Source: http://feeds.slate.com/click.phdo?i=75f097d86b452d20c053f37fafb37fd0

kanye west theraflu joey votto the masters live mega millions winner holy thursday chris stewart evo 4g lte

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.